Dr Barbara Kunz is a research project officer working in the geochemistry lab of the School of Environment, Earth and Ecosystem Sciences at the Open University (OU). Her work focuses on analysing samples with a machine called a Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer. This machine analyses solid materials for their trace element composition.

Dr Barbara Kunz is a research project officer working in the geochemistry lab of the School of Environment, Earth and Ecosystem Sciences at the Open University (OU). Her work focuses on analysing samples with a machine called a Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer. This machine analyses solid materials for their trace element composition.

Currently she is working on a large Natural Environment Research Council project. The aim of the project is to understand why some volcanoes form metal deposits and others do not. This is important to ensure future supplies of the critical metals needed in modern technology for things like batteries, mobile phones and computers.

You can catch Barbara on her soapbox as part of Soapbox Science Milton Keynes on 29th June, where she will be talking about “How to read rocks; from tiny observations to big conclusions”.

Follow Barbara on Twitter: @KunzBE

SS: Barbara, how did you get to your current position?

BK: After I finished my PhD I was looking for jobs in academia and saw the job ad on Twitter. A mentor and friend of mine who works at the OU encouraged me to apply, even though my skills didn’t exactly match the advertisement. The application deadline was shortly after a scientific conference I was attending. So, after a full day of conference talks and posters, I sat down that night to work on my CV and covering letter. The hard work paid off as I got the job!

SS: What, or who, inspired you to get a career in science?

BK: My parents, who both studied physics, and other relatives played a large role in inspiring me to get into science. I have numerous childhood memories where I developed my scientific skills – observing and describing things, connecting my observations, and drawing conclusions. Many everyday activities were flavoured with activities like these.

However, when I needed to decide what I wanted to do at uni, I was torn between my love for science, and a passion for art and creativity. When the time came to make a decision I went with geology, which allowed me to combine science and being outdoors. I’ve never regretted my decision, and during my undergrad degree I realised that I wanted to pursue a career in science.

SS: What is the most fascinating aspect of your research/work?

SS: What is the most fascinating aspect of your research/work?

BK: Looking back millions and millions of years into the past, as well as investigating places deep within the earth via samples brought to the surface by volcanoes or mountain-building processes. This allows us to access areas usually inaccessible to human beings. I also think that the hidden worlds revealed under a microscope are fascinating.

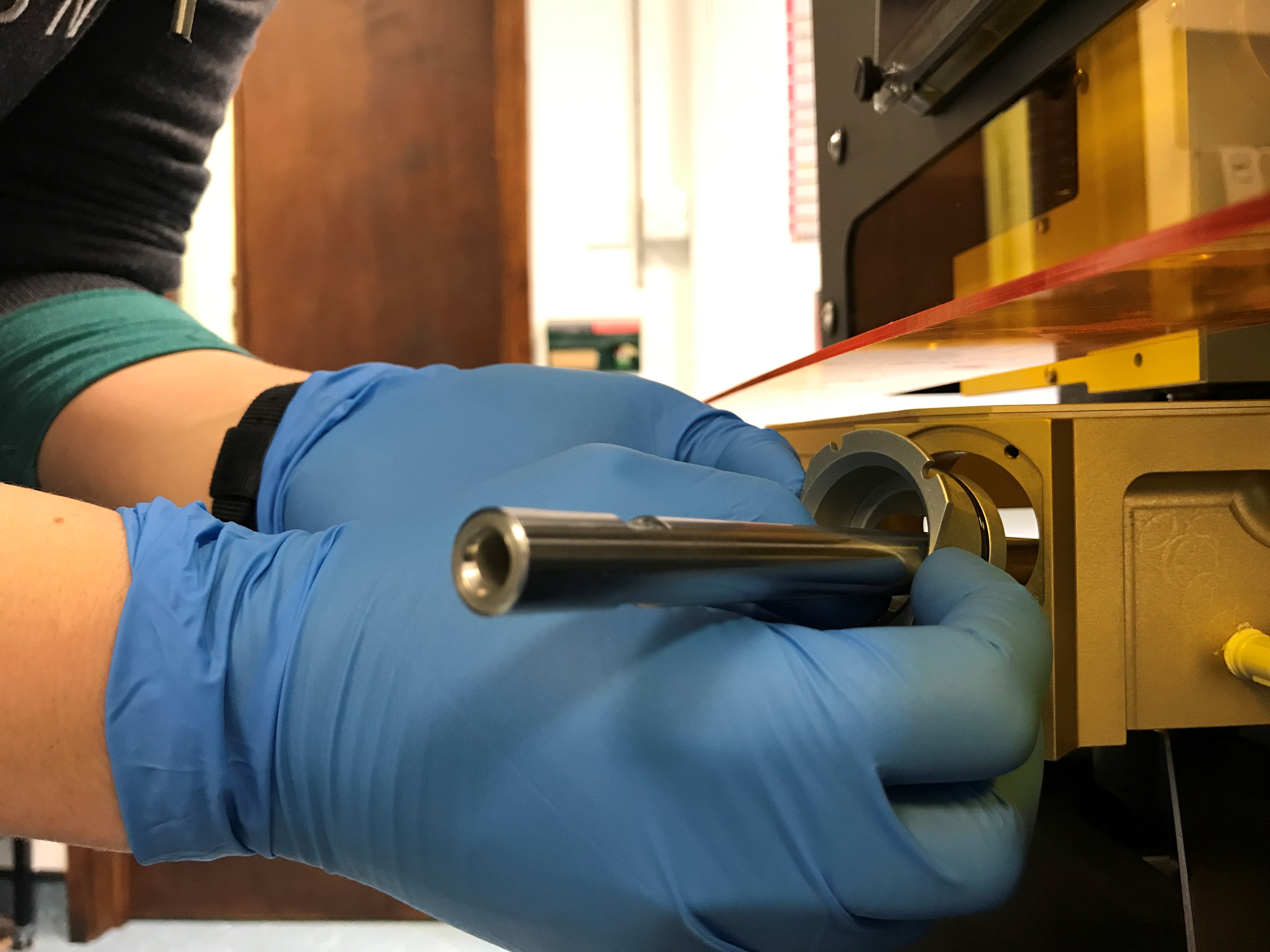

Something that really grew on me with time are the technical aspects of the instruments geologists use to measure their samples. In addition to using the instruments, these days it’s part of my job to maintain and troubleshoot them.

SS: What attracted you to Soapbox Science in the first place?

BK: I saw two PhD students from my department talking at a Soapbox Science event last year. It looked like a fun challenge. I think public engagement is important, especially in this day and age of fake news and climate change deniers. However scientists are often not specifically trained in this. As if by magic we are expected to do great research, deliver brilliant lectures, write publications and grant applications, be a whizz at administrative work, and do public engagement. Our formal education covers only some of these skills. So for me, Soapbox Science is a great training opportunity. I will learn how to present my research to a general audience, and thereby help them understand why my job is important, and why it is important to be financed by taxpayers’ money.

SS: Sum up in one word your expectations for the day

BK: Challenge. I think it takes courage to talk in front of an audience. It might seem contradictory, but explaining the often complex or abstract work I am doing to a non-expert audience is even more difficult and challenging than talking at a scientific conference.

SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be?

BK: I think equality and diversity in science are definitely issues that need confronting. No matter what their race, gender, sexuality or economic background, the more diverse the people working in science, the more diverse the ideas and approaches to solve the challenges we face in the modern world will be.

Another big topic in academia is the need to address stress levels and mental health issues. This is a huge issue which often gets glossed over, or seen as a badge of honour. Currently, the discussion focuses mostly on what the individual can do (work-life balance, personal stress reduction/resilience, meditation, yoga, etc.). However I think that can only be one side of the equation. The other side is the need for structural changes within university systems to reduce stress and create a more healthy work culture.

SS: What would be your top recommendation to a woman studying for a PhD and considering pursuing a career in academia?

BK: Networking and supporting each other. Academia is often lonely enough without the added isolation created by rivalry and/or mistrust. Additionally, I would encourage women to apply for jobs, awards, grants etc. even if they feel they are not totally qualified. There are scientific studies that show that women only apply when they are 100% qualified, but that men apply when they are 60% qualified (https://hbr.org/2014/08/why-women-dont-apply-for-jobs-unless-theyre-100-qualified). If we women want to be equally as successful as men I think we need to be more confident in our skills and abilities, or simply dare to be bolder.