Sariqa Wagley is a researcher at the University of Exeter in the Biosciences department where she works on bacterial pathogens affecting human health. Here she narrates her route through education, talks to us about the challenges facing women and those from underprivileged backgrounds in science, discloses her favourite bacteria and tells us what Soapbox Science means to her. You can come and meet Sariqa in Exeter on the 22nd of September when she gets on her soapbox in the centre of town!

Sariqa Wagley is a researcher at the University of Exeter in the Biosciences department where she works on bacterial pathogens affecting human health. Here she narrates her route through education, talks to us about the challenges facing women and those from underprivileged backgrounds in science, discloses her favourite bacteria and tells us what Soapbox Science means to her. You can come and meet Sariqa in Exeter on the 22nd of September when she gets on her soapbox in the centre of town!

What it means to be a woman from an under privileged background in science

By Sariqa Wagley

How did I get into science? Pull up a pew…

I am a Muslim Asian woman who grew up in Luton (Bedfordshire). At high school I was one of the brightest students in the year and I enjoyed school thoroughly and finished with great GCSE results. I carried out voluntary work at the local hospital and it was then I knew I wanted to study health and disease in some form. Both my parents had limited access to education in India but understood that a good education would lead to good job prospects and more opportunities. They placed a heavy emphasis on education and schooling and pushed me and my siblings to go to university. However, being from a low income family this was not an easy task. The year I was to start university the government scrapped maintenance grants for those studying in higher education. My parents were against taking out student loans with a fear that I may not be able to pay it back and would be faced with a debt early in life. I realised that if I was going to go to university I was going to have to start earning money. I found a part time job in the final year of high school and started saving my money to help pay for university. I went to the local sixth form college and I found myself struggling straight away to keep on top of my studies. I managed to scrape through my A-levels and got a place at Surrey University to study Medical Microbiology. I had to carry on working in the first year to help pay my way and again during the course I found myself struggling to stay on top of things.

When I finished my first year with a mere 50% overall I was totally disheartened and dismayed at my progress or lack of! I went to see my personal tutor and slumped in a chair in his office I remember listening to him go through some of my exam papers and tell me how I had failed to grasp the questions in my exam and answer them properly. After a while, I think he must have felt sorry for me as he changed his tone and started asking me what I wanted to do and why was I at university. I told him about my interest in science, what motivated me about my course, I told him about my parents who pushed me to have the best education and that having a university degree was key to that. I told him I didn’t have much money and that I had a part time job working Wednesdays (the day students have free for extracurricular activities) and weekends. It was then he made some critical changes that pretty much changed how my career went. He sent me on an extra tuition course aimed for foreign students and made me attend an essay writing course. He encouraged me to reduce my hours on my job and gave me some extra reading to do around my modules. I felt a little insulted and an incredible amount of shame thinking how could I possibly need all this extra help when I had been the top of my school only three years previous. The feeling of being somewhere I didn’t belong was hitting me hard and being surrounded by top students, who seemed to know and have everything, I felt like the outsider.

A report by the Sutton Trust published in 2008 on ‘Increasing higher education participation amongst disadvantaged young people and schools in poor communities’ stated that 60,000 pupils (10% of the cohort) who at some point were among the top fifth performers in their school, still failed to enter higher education by the age of 19. Furthermore, 70% of 11-16 year olds from disadvantaged backgrounds said they would go into higher education, but the reality of students choosing to go to university was lower. The main reasons for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds not continuing their further education was their need to start earning, avoid debt and they felt disillusioned with formal learning. Furthermore, those in poorer families lacked the support from their peer groups and families and the aspirations were lower in how far they could go with their education.

Now many years later, it is easy for me to say I came through that second year at university with an overall 60%, which was a huge improvement. But in reality, I had to face some hard facts about whether I was suited for higher education and I had to take on board a lot of practical advice to change my circumstances which was not easy. I recognise those findings from the Sutton Report in my own experience and realise that had I not had the support of my tutor (Late Dr Tony Chamberlain) at Surrey University I would most probably have dropped out sometime in my second year.

In 2003, I carried out my industrial placement year at a government science lab called Cefas in Weymouth working on human pathogens which sealed my future as a microbiology scientist. The good news was I saved enough money from my industrial placement to ditch my part time job in my final year and so I could concentrate fully on my studies. I finished with a 2:1 degree in Medical Microbiology and was offered a PhD at Cefas for 4 years to carry out research in microbiology. Due to the struggles I had faced prior to and during my degree; graduating was a very proud moment for me.

Is it all plain sailing from here? Well….

I finished my PhD and came to work at the University of Exeter as a post doc. Here, I found the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) students make up 20% of the undergraduate student cohort (data for 2016) which is a smaller proportion of the UK cohort than other Russell Group universities. The number of staff from BAME groups in Biosciences where I am based is a low 8% in 2016/2017. Recently, the University of Exeter came into the headlines, when a number of students were expelled following allegations of racism, sexism, and homophobia towards other students. Earlier this year, at Nottingham Trent University, a black student captured the moment on video when she was forced to hide in her dorm room while being subjected to a tirade of racist abuse from other students. Given the environment that students and sometimes staff encounter on higher education campuses the low uptake numbers of BAME students and staff at University of Exeter does not surprise me. I have accepted that getting into and surviving in academia for people of BAME and/or from disadvantaged backgrounds is still not an easy task and more needs to be done to change the environment that students and staff are being recruited into.

2016/2017 data for academic career progression pipelines in Biosciences (Exeter University)

Discrimination on higher education campuses is not limited to amongst the student body. There is a significant amount of inequality in career progression through academia which I had not been prepared for. At undergraduate level there are more females (63%) than males (37%) in Biosciences at the University of Exeter. As the academic progresses through their career trajectory the number of males and females are even until they reach a tenure position i.e. a permanent position with a university. At this point the balance shifts and the number of female staff drops dramatically and becomes male biased. The key question for me when I heard these facts were ‘what is happening to all these women and why are they dropping out?’

So why are women dropping out?

Some researchers are focusing on women’s choices to explain the number of women dropping out of the work force in STEM subjects. Unfortunate terms such as the ‘Opt-Out’ idea coined by the New York Times in 2003 suggests that some women in successful jobs once they reach around 30 – 40 years old decide to opt-out of their careers usually to spend more time with their families. These women who ‘Opt-Out’ state that it was not due to discrimination or other barriers in the workplace, but because it was their choice to do so and that they choose different things to men. I do not agree with this ill-termed ‘Opt-Out’ idea as it has not been very easy for me to get to where I am in my career and as an early career researcher hearing that independent educated women chose to drop out or leave academia is hard to grasp. The problem with the ‘Opt-Out’ idea is that the onus or blame for the low levels of women in higher positions in the workplace is put solely on women and the root of these patterns remains ignored.

Breaking down gender stereotypes in academia and changing structural barriers that face women such as policies around maternity and paternity leave, recruitment, promotion, leave taking and decision making within departments are all important factors that are or have been hindering women’s career progression. I also believe, that continued unconscious biases in academic culture are predisposing men for career success and leaving women in the side lines. These biases include ideas such as ‘working mums’ are not committed to their careers, or that women are too emotional, that women speak too softly, women who show high levels of emotional intelligence cannot be effective in leading, and ideas like ‘men are the born leaders’ and women are just seen as bossy when take charge. These biases are exasperated by the high emphasis on winning and securing funding which can be a significant hindrance to both men and women in academia. As a consequence women are missing out on good jobs with good salaries and long term the academic environment is losing a wide talent pool of female scientists that bring diversity in different thought process’ and research talent.

Who am I now and what am I doing in science?

It is has been over 10 years since I finished my university degree and I have been a research scientist at the University of Exeter since 2008. I work on understanding how bacteria cause disease in humans and what weapons they have to make us sick. By doing this research I can help make informed decisions about strategies for detection, prevention and cure of bacterial infections in humans. I have worked on a number of different bacteria that make people sick and my favourite is called Vibrio parahaemolyticus. It causes gastroenteritis when people eat raw or under cooked shellfish that are contaminated with this bacterium. In 2016, I won a significant BBSRC research grant to study this pathogen and I am now studying how V. parahaemolyticus enters a dormant or sleep-like state when faced with stressful conditions and how it reawakens from this sleep when those conditions around them become more favourable. This is a clever defence strategy that bacteria have to help them survive adverse conditions and environments. I love my job as a researcher and enjoy making new discoveries and having an impact in the real world. I get to work with top scientists from institutes such as Cefas, FDA, DSTL, Natural History Museum, and defence agencies in the USA. I have been fortunate enough to travel (one of the perks of the job) and present my research to people all over the world including Europe, Thailand, USA, New Zealand and Australia. I am currently applying for fellowships which would secure me a permanent position in academia. I know I still have a long way to go before I will be truly satisfied I have made it in science. But if it had not been for my own personal determination, and encouragement from my parents and support from my tutor at university, I would not have been able to contribute to science and society in the way that I have.

What attracted me to Soapbox Science in the first place?

I believe that all young people should have a chance to enter higher education regardless of their background and gender or where they live. At the University of Exeter, the Centre for Social Mobility is there to help support students from disadvantaged groups and realise their potential through higher education. There is widening participation and access programmes that are geared to increasing uptake of BAME students and those from disadvantaged groups and I hope the University of Exeter can increase their targets in this area by using these programmes to maximise the best effects. But to really encourage students from these backgrounds into STEM subjects requires people from those groups that have had some success to create a presence in society and break down existing stereotypes. Which is why I wanted to take part in Soapbox Science. I wish I had had access to programmes like Soapbox Science when I was growing up or some scientist role models to aspire to. Soapbox Science is a fantastic initiative that supports female scientists all around the country and helps provide these much needed role models for young people who may be considering a career in the STEM subjects. It is important to me that young people in the same situation that I was in, realise that a career in science is possible for them too.

I believe that all young people should have a chance to enter higher education regardless of their background and gender or where they live. At the University of Exeter, the Centre for Social Mobility is there to help support students from disadvantaged groups and realise their potential through higher education. There is widening participation and access programmes that are geared to increasing uptake of BAME students and those from disadvantaged groups and I hope the University of Exeter can increase their targets in this area by using these programmes to maximise the best effects. But to really encourage students from these backgrounds into STEM subjects requires people from those groups that have had some success to create a presence in society and break down existing stereotypes. Which is why I wanted to take part in Soapbox Science. I wish I had had access to programmes like Soapbox Science when I was growing up or some scientist role models to aspire to. Soapbox Science is a fantastic initiative that supports female scientists all around the country and helps provide these much needed role models for young people who may be considering a career in the STEM subjects. It is important to me that young people in the same situation that I was in, realise that a career in science is possible for them too.

References:

Report to the National Council for Educational Excellence, The Sutton Trust, 2008. https://extra.shu.ac.uk/higherfutures/digest/misc/report_suttontrust.pdf

Equality data at Exeter University http://www.exeter.ac.uk/staff/equality/equalitydata/

Exeter University expels students over racism row, The Guardian, 2011 https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/may/01/exeter-university-expels-students-over-racism-row

Police arrest two 18-year-old men over racist chanting outside Nottingham Trent University student’s bedroom, The Telegraph, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/2018/03/08/police-arrest-two-18-year-old-men-racist-chanting-outside-nottingham/

Academic career progression pipelines in Biosciences http://lifesciences.exeter.ac.uk/athenaswan/

The Opt-Out Revolution, New York Times by Lisa Belkin, 2003. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/26/magazine/the-opt-out-revolution.html

Alexandra Klein (@aexolowski), Max Planck Insitute of Neurobiology, is taking part in Soapbox Science Munich on 1 June 2019 with the talk:“An Anxious Island in the Brain – Die Ängstliche Insel des Gehirns“

Alexandra Klein (@aexolowski), Max Planck Insitute of Neurobiology, is taking part in Soapbox Science Munich on 1 June 2019 with the talk:“An Anxious Island in the Brain – Die Ängstliche Insel des Gehirns“

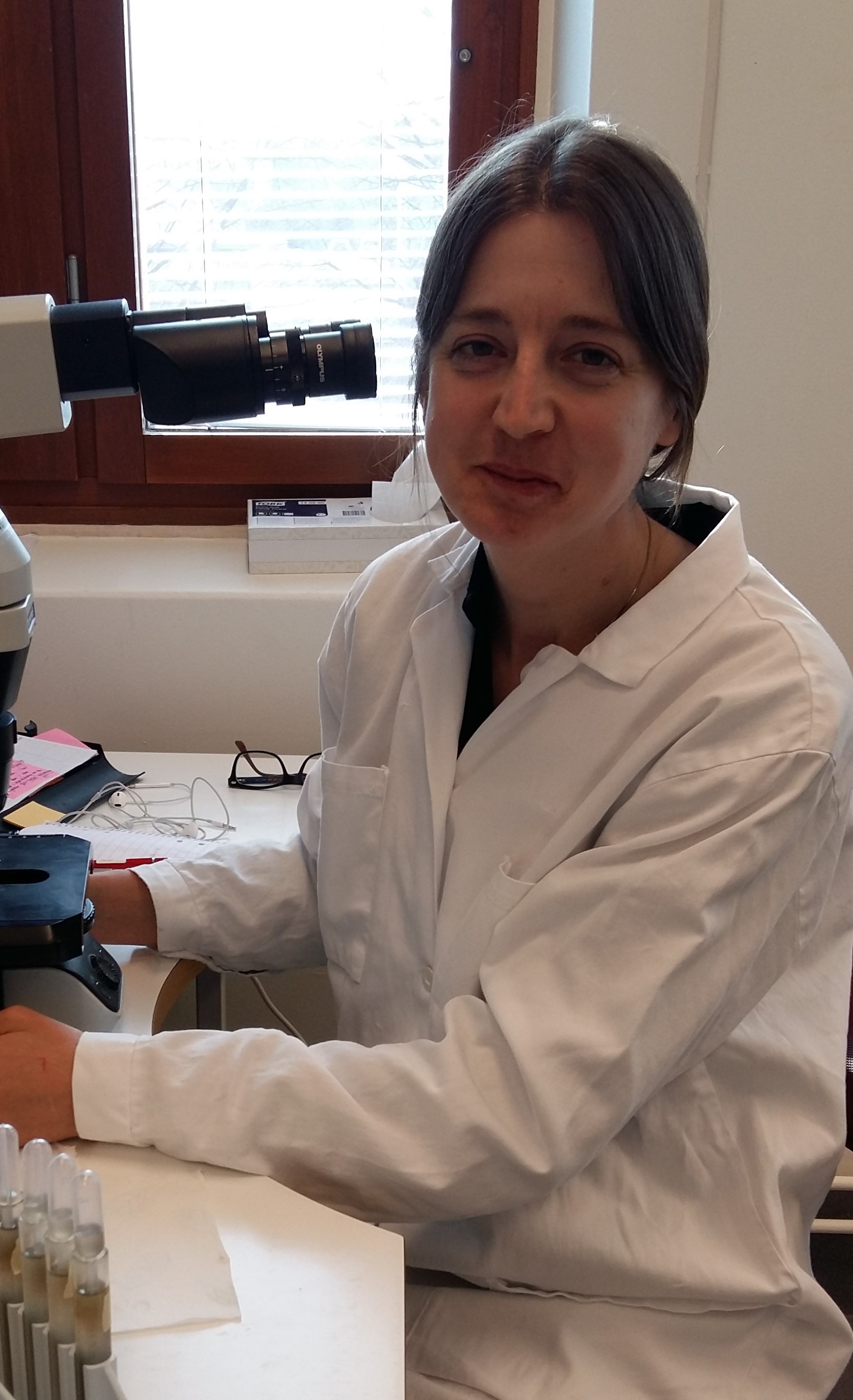

Maria Kahlert is an Associate Professor in biology with specialisation in ecology. Her research focuses on freshwater benthic algae; their biodiversity, how they are regulated by environmental factors, and how they can be used as biomonitors in lakes and streams. Maria Kahlert will take part in the

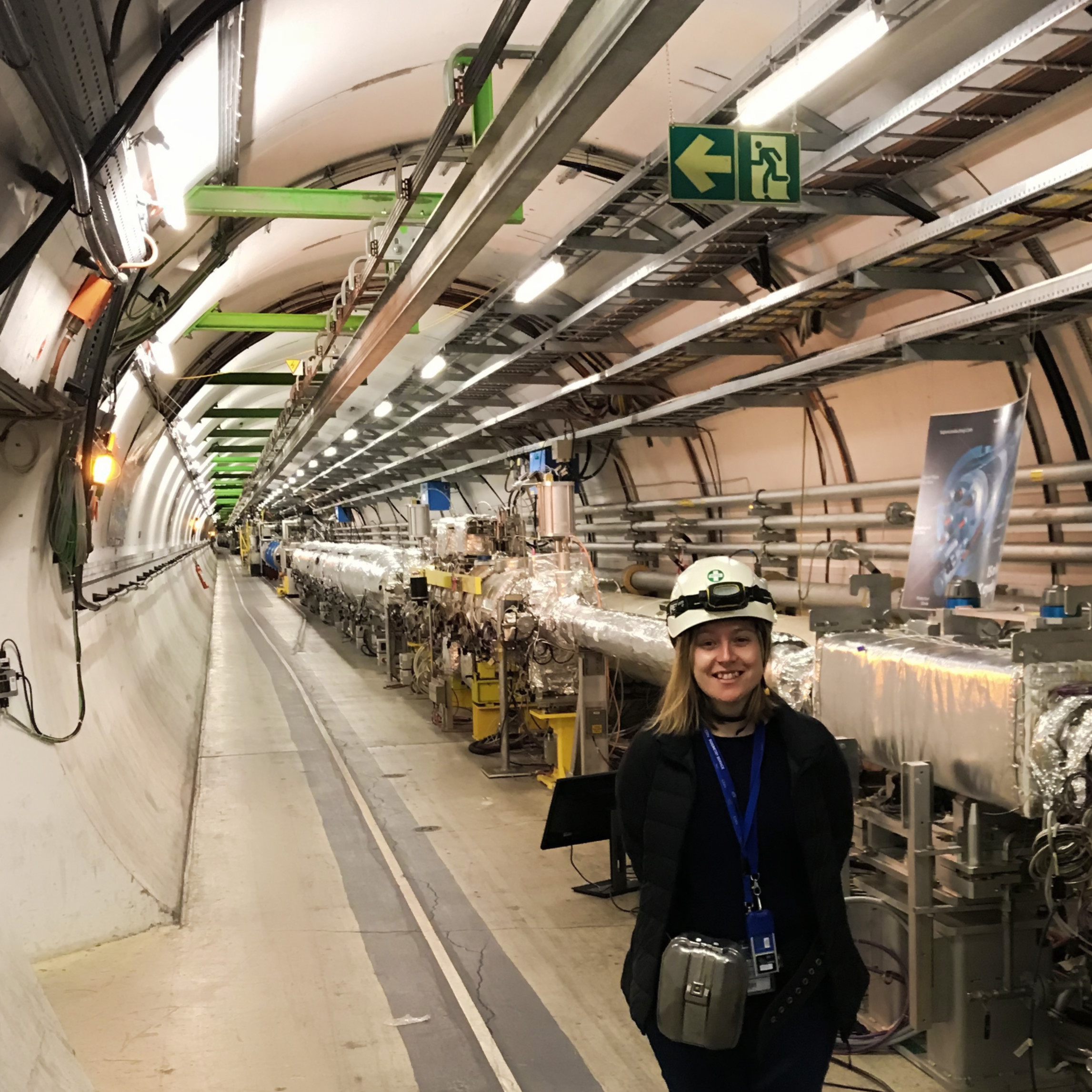

Maria Kahlert is an Associate Professor in biology with specialisation in ecology. Her research focuses on freshwater benthic algae; their biodiversity, how they are regulated by environmental factors, and how they can be used as biomonitors in lakes and streams. Maria Kahlert will take part in the Rebeca Gonzalez Suarez is a Spanish particle physicist that works at Uppsala University in Sweden where she teaches physics in the Department of Engineering Sciences. Now a member of the ATLAS Collaboration at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) since 2018, she started her career in the CMS Collaboration (2006-2018). A Higgs boson and top quark expert, today she keeps trying to find answers to long standing questions in the field searching for new phenomena at the LHC. At the

Rebeca Gonzalez Suarez is a Spanish particle physicist that works at Uppsala University in Sweden where she teaches physics in the Department of Engineering Sciences. Now a member of the ATLAS Collaboration at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) since 2018, she started her career in the CMS Collaboration (2006-2018). A Higgs boson and top quark expert, today she keeps trying to find answers to long standing questions in the field searching for new phenomena at the LHC. At the

Emelie Pettersson is a veterinarian and a PhD student at the National Veterinary Institute and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. After graduating with a veterinary degree from the University of Melbourne, Australia in 2008 she spent almost nine years working in mainly small animal emergency and critical care medicine, both in Australia and in Sweden. With a desire to eventually work in the field of veterinary public health, Emelie did a Master of Science degree in International Animal Health through the University of Edinburgh, parallel to her clinical work, and graduated in 2014. In 2017, she started a PhD in veterinary parasitology and the career path took a new turn, from the emergency room with dogs and cats to pig farms and the laboratory, investigating the parasites of pigs.

Emelie Pettersson is a veterinarian and a PhD student at the National Veterinary Institute and the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. After graduating with a veterinary degree from the University of Melbourne, Australia in 2008 she spent almost nine years working in mainly small animal emergency and critical care medicine, both in Australia and in Sweden. With a desire to eventually work in the field of veterinary public health, Emelie did a Master of Science degree in International Animal Health through the University of Edinburgh, parallel to her clinical work, and graduated in 2014. In 2017, she started a PhD in veterinary parasitology and the career path took a new turn, from the emergency room with dogs and cats to pig farms and the laboratory, investigating the parasites of pigs. What is different with Swedish housing conditions for pigs?

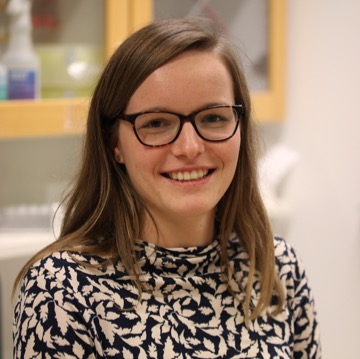

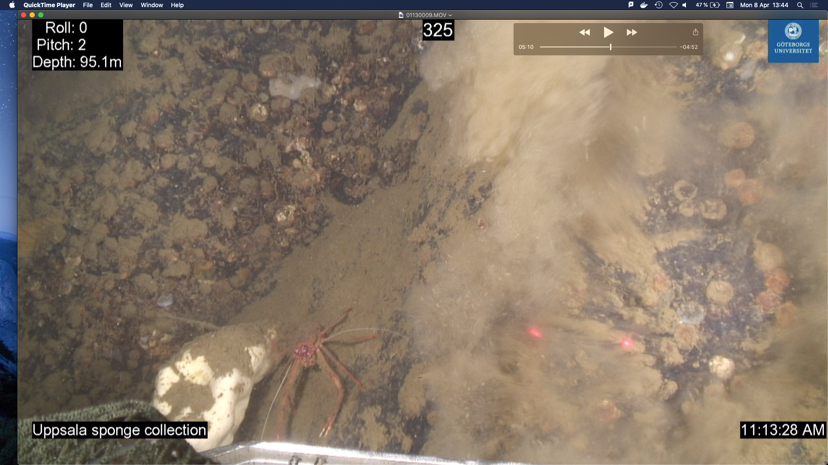

What is different with Swedish housing conditions for pigs?  Karin Steffen, is a doctoral student at Uppsala University. She has a background in biology from Albert-Ludwigs University in Freiburg, Germany and Uppsala University, Sweden. For her doctoral studies, she investigates natural product diversity in a deep-sea sponge. To this end, Karin uses different “-omics” (genomics and metabolomcis) and explores computational tools to integrate big data. Karin Steffen will take part in the

Karin Steffen, is a doctoral student at Uppsala University. She has a background in biology from Albert-Ludwigs University in Freiburg, Germany and Uppsala University, Sweden. For her doctoral studies, she investigates natural product diversity in a deep-sea sponge. To this end, Karin uses different “-omics” (genomics and metabolomcis) and explores computational tools to integrate big data. Karin Steffen will take part in the

Jessica Brown is in her second year as a PhD student in the XM2 Metamaterials Centre of Doctoral Training at the University of Exeter, where she is working on a project on acoustic microfluidics and phononic crystals. Here she tells us how her passion for physical science led her to her current position and what inspires her to strive in her field. Hopefully you caught Jessica’s talk at

Jessica Brown is in her second year as a PhD student in the XM2 Metamaterials Centre of Doctoral Training at the University of Exeter, where she is working on a project on acoustic microfluidics and phononic crystals. Here she tells us how her passion for physical science led her to her current position and what inspires her to strive in her field. Hopefully you caught Jessica’s talk at

Dr. Monika Bokori-Brown is a research fellow at the University of Exeter where she studies bacterial toxins. Here she tells us about her work, what inspires her most and why she decided to take part in Soapbox Science. You can come and hear Monika speak at

Dr. Monika Bokori-Brown is a research fellow at the University of Exeter where she studies bacterial toxins. Here she tells us about her work, what inspires her most and why she decided to take part in Soapbox Science. You can come and hear Monika speak at

Kirsten Thompson is a marine mammal geneticist and Associate Research Fellow at the University of Exeter. Here she describes her fascinating journey into science and the challenges of her next step. You can come and meet Kirsten and hear her speak about her work with deep diving marine mammals at

Kirsten Thompson is a marine mammal geneticist and Associate Research Fellow at the University of Exeter. Here she describes her fascinating journey into science and the challenges of her next step. You can come and meet Kirsten and hear her speak about her work with deep diving marine mammals at

Soraya Meftah is a PhD Student based at the University of Exeter and Bristol, funded by the MRC GW4 Biomed DTP. Her current research focuses on early changes in connections between neurons in Alzheimer’s Disease. She does this using electrophysiology and multi-photon microscopy (measures electricity in the brain and looks at it using a really powerful laser beam!). Come and meet Soraya this Saturday at

Soraya Meftah is a PhD Student based at the University of Exeter and Bristol, funded by the MRC GW4 Biomed DTP. Her current research focuses on early changes in connections between neurons in Alzheimer’s Disease. She does this using electrophysiology and multi-photon microscopy (measures electricity in the brain and looks at it using a really powerful laser beam!). Come and meet Soraya this Saturday at

Sariqa Wagley is a researcher at the University of Exeter in the Biosciences department where she works on bacterial pathogens affecting human health. Here she narrates her route through education, talks to us about the challenges facing women and those from underprivileged backgrounds in science, discloses her favourite bacteria and tells us what Soapbox Science means to her. You can come and meet Sariqa in

Sariqa Wagley is a researcher at the University of Exeter in the Biosciences department where she works on bacterial pathogens affecting human health. Here she narrates her route through education, talks to us about the challenges facing women and those from underprivileged backgrounds in science, discloses her favourite bacteria and tells us what Soapbox Science means to her. You can come and meet Sariqa in

I believe that all young people should have a chance to enter higher education regardless of their background and gender or where they live. At the University of Exeter, the Centre for Social Mobility is there to help support students from disadvantaged groups and realise their potential through higher education. There is widening participation and access programmes that are geared to increasing uptake of BAME students and those from disadvantaged groups and I hope the University of Exeter can increase their targets in this area by using these programmes to maximise the best effects. But to really encourage students from these backgrounds into STEM subjects requires people from those groups that have had some success to create a presence in society and break down existing stereotypes. Which is why I wanted to take part in Soapbox Science. I wish I had had access to programmes like Soapbox Science when I was growing up or some scientist role models to aspire to. Soapbox Science is a fantastic initiative that supports female scientists all around the country and helps provide these much needed role models for young people who may be considering a career in the STEM subjects. It is important to me that young people in the same situation that I was in, realise that a career in science is possible for them too.

I believe that all young people should have a chance to enter higher education regardless of their background and gender or where they live. At the University of Exeter, the Centre for Social Mobility is there to help support students from disadvantaged groups and realise their potential through higher education. There is widening participation and access programmes that are geared to increasing uptake of BAME students and those from disadvantaged groups and I hope the University of Exeter can increase their targets in this area by using these programmes to maximise the best effects. But to really encourage students from these backgrounds into STEM subjects requires people from those groups that have had some success to create a presence in society and break down existing stereotypes. Which is why I wanted to take part in Soapbox Science. I wish I had had access to programmes like Soapbox Science when I was growing up or some scientist role models to aspire to. Soapbox Science is a fantastic initiative that supports female scientists all around the country and helps provide these much needed role models for young people who may be considering a career in the STEM subjects. It is important to me that young people in the same situation that I was in, realise that a career in science is possible for them too.