Eugenia Pyurbeeva (part of @lab_mol), Queen Mary University of London, is taking part in Soapbox Science London on 25th May 2019 with the talk:“Heat engines: from steam trains to using quantumness as a resource”

Eugenia Pyurbeeva (part of @lab_mol), Queen Mary University of London, is taking part in Soapbox Science London on 25th May 2019 with the talk:“Heat engines: from steam trains to using quantumness as a resource”

Soapbox Science: How did you get to your current position?

Eugenia Pyurbeeva: In a surprisingly straightforward way, but being a first-year PhD student is not much of a position. I’ve always loved science, got into a Maths-specialised school in secondary school, spent hours after school in the Physics lab there, partly doing experiments and solving problems and partly hanging out with a group of others who stayed there and then got through combined six years of Bachelors and Masters still having the idea that I love science and want to do research.

SS: What, or who, inspired you to get a career in science?

EP: A lot of things and people.

I read a lot of books, watched some films and wanted to be the hero. Being a type of hero who fights ten enemies at a time with brute force was never very appealing and also out of the question with me being small, completely unathletic and quite socially awkward. So the most plausible and appealing heroic type was scientific: Sherlock Holmes, Doctor Who, Captain Nemo, Ghostbusters, and particularly Cyrus Smith from the Mysterious Island, obviously a very tempting career prospect.

As for real people, whoever told me that it’s not that water boils at 100C, it’s that 100C is the temperature at which water boils (I honestly don’t remember who it was, but it was a very important sentence in my life), my mum, who allowed me to play with any dangerous object and drop ballet for electronics, my grandad, who I used to believe was an astronaut and flew off to space every morning at nine, only to return home in time for dinner (he was an aerospace engineer, really) and had a very appealing storage room (see below), my Maths teacher at school, who taught me how to read properly, everything, including poetry. And most importantly a Physics teacher, who never had me in his class, but was always happy to stay after lessons to show me a problem or one of his “toys” — the collection now includes all the good items from the gift shops of most science museums in the world, with whom I’ve worked for six years in after-school clubs and who is still happy to listen to my ramblings about being stuck on something and ask very good questions. He is the best question-asker I’ve ever met.

SS: What is the most fascinating aspect of your research/work?

EP: The process of the work itself.

When I was about ten, I got an electronic kit where you could make different circuits using a springboard and ordinary electronic parts. I had one before that had plastic bits that snapped together, but this one fascinated me, because unlike Lego or the first kit, you didn’t have to buy a new set to have more parts and build new circuits, the parts could be found in old TVs or cassette players that neighbours put next to the rubbish bins (I quickly learnt do desolder), pinched from my grandads storage room and even bought separately in a shop! Also, to find new circuits to build, you had to ask grandad for his old Electronics magazines, buy books or later search online. It still felt like playing with a kit, but an ever expanding kit with parts and instructions you had to search for around you, which only added to the fun.

Later, my school had a system for teaching Maths where you got a problem sheet and got through it at your own pace discussing the solved problems with a teacher. I loved it and it also felt like a game, with set time frames, rules and a bit of competition (you knew what problem or sheet your friends were on, so putting in a few extra hours got you ahead, unless they did the same).

It became an infinitely more interesting game when I realised I can set my own problem sheets for myself. Problems, sub-problems, do this in case of that, I still nearly always write myself a problem sheet when I do science. Only now it includes checking something with an experiment, doing an online search to find something out, going to the library to look for an obscure undigitised article, even talking to a someone about a problem and writing down ideas — instead of a kit it’s an ever-expanding never-ending quest-like game that can be played anywhere and includes most of your environment.

What’s not to like? It is a bit like the beginning of an Indiana Jones film (The Last Crusade) where reading a notebook leads to a trip to a library in Venice, finding a cross on the floor and a journey through rat-infested catacombs (apart from the rats, but I’m fine with that).

SS: What attracted you to Soapbox Science in the first place?

EP: I always enjoy events that bring music or art to the streets. Even if I don’t like this particular art or music, it makes walking around the city much more enjoyable and reminds you that people around are not just some grey mass you have to squeeze through on the tube, but separate interesting individuals who spend a lot of time and effort to create this beautiful music or for some weird reason cover trees with colourful knitting. I believe science to be an art form in the sense that it is a skilled work to create something intrinsically beautiful, so I love the idea of “busking” science and it is a good challenge to try and show the beauty in it to people passing by.

Also, I just like to talk rather loudly about things that interest me.

SS: Sum up in one word your expectations for the day

EP: Handwaving. Both as a means of explanation and in a happy sort of way.

SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be?

SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be?

EP: Education. I can talk at great lengths about it, but would try to keep it short.

I’d love to see more real scientists teaching at secondary school level — not one-off outreach activities that are done and then quickly forgotten, but proper teaching at school in the way they would have liked to be taught themselves. Without drilling for tests, because it doesn’t teach anything (or enough for the time it takes), without making it less demanding in fear it would be boring — it would be, but learning to work hard in anything is probably even more important than science, and definitely without shunning from experiments and hands-on work in fear of Health and Safety (it is important, but I’ve seen too many instances when children do the “sink of swim” experiment time after time because it’s the safest thing you can do and ticks the “hands on” box). We are, after all, apes with intricately evolved hands specifically for manipulating objects and learning from that — and I feel that fitting this bit to that one with bits of wire and some string in such a way that it wouldn’t get tangled with the third bit should definitely be part of the curriculum. It would mean a few cuts and burns, but it is worth it.

On the other hand, it is great for the teacher as well. I’ve taught in various after-school clubs since I was fifteen (one involved making a Gauss gun that could shoot a sharpened nail through a tin can, but I won’t do it again) and keeping the school curriculum and quite a bit (in order to be able to answer most questions you might encounter) helps a lot with not shutting up in your narrow specialty and the mental exercise of finding a mistake in somebody’s solution one second and thinking of a good example for something else the next is honestly very good for you.

SS: What would be your top recommendation to a woman studying for a PhD and considering pursuing a career in academia?

EP: I’m definitely not in a position to give any recommendations about it. I’d like some advice myself, though.

Julia Potocnjak, University of Colorado- Boulder, took part in the first ever Soapbox Science Boulder event on 7th April 2019, with the talk:“Gummy Bears don’t wear Genes! How Genetics Works”

Julia Potocnjak, University of Colorado- Boulder, took part in the first ever Soapbox Science Boulder event on 7th April 2019, with the talk:“Gummy Bears don’t wear Genes! How Genetics Works” SS: What attracted you to Soapbox Science in the first place?

SS: What attracted you to Soapbox Science in the first place? SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be?

SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be? SS: What would be your top recommendation to a woman studying for a PhD and considering pursuing a career in academia?

SS: What would be your top recommendation to a woman studying for a PhD and considering pursuing a career in academia?

Dr Danielle Solomon

Dr Danielle Solomon Professor Frances A Edwards, University College London, is taking part in

Professor Frances A Edwards, University College London, is taking part in  Eugenia Pyurbeeva

Eugenia Pyurbeeva SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be?

SS: If you could change one thing about the scientific culture right now, what would it be?

Dr Stella Manoli

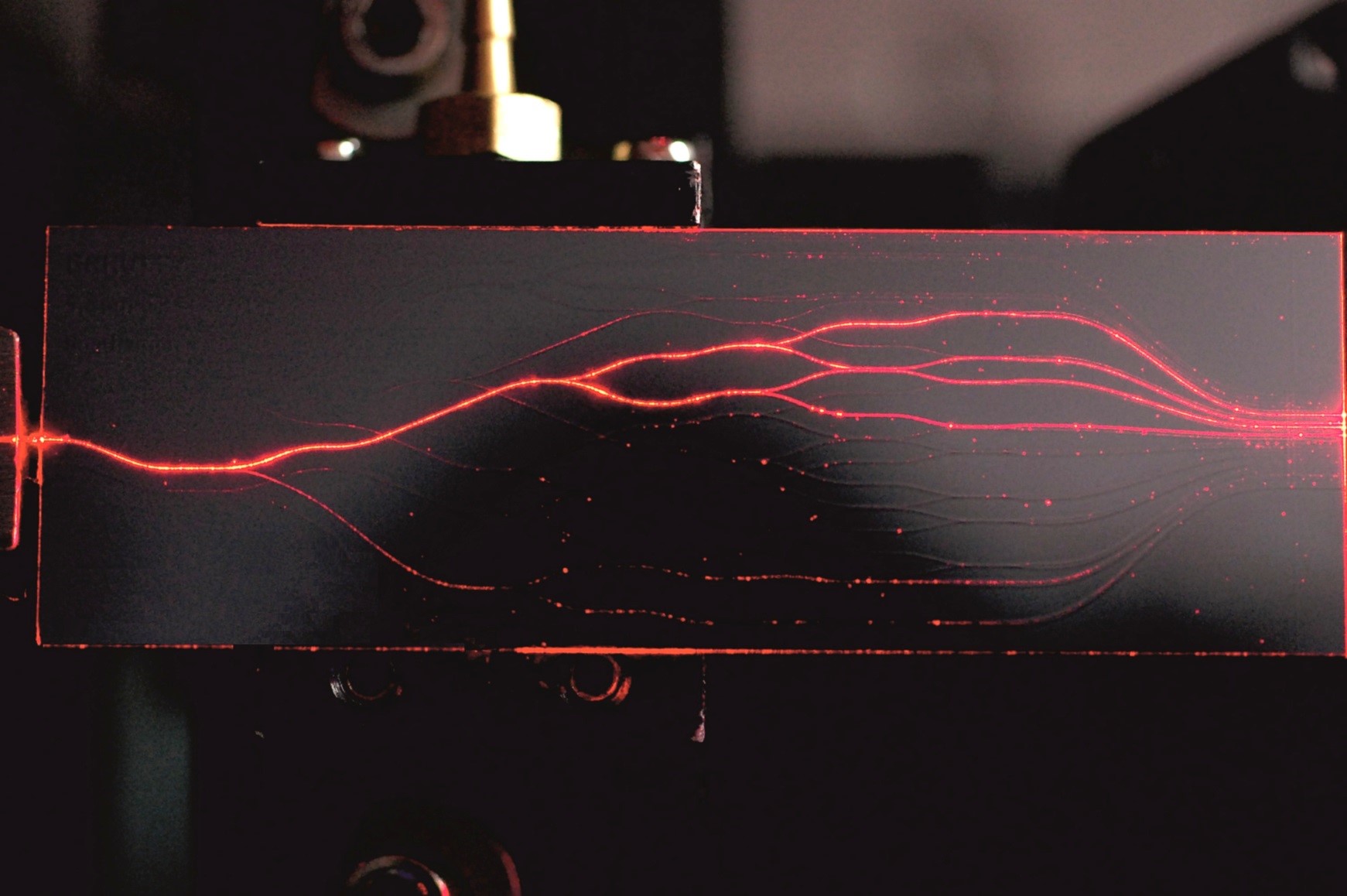

Dr Stella Manoli Figure 1: Optical fiber

Figure 1: Optical fiber Figure 2: Computer chips for quantum applications

Figure 2: Computer chips for quantum applications Fiona Scott

Fiona Scott Dr. Estefania Munoz Diaz

Dr. Estefania Munoz Diaz